Somewhere, according to Taoist belief, far out in the ocean, lie a series of mysterious islands where the immortals dwell – remote, unreachable, and radiant with otherworldly serenity. This myth, carried across seas and centuries, finds a delicate echo in Japanese folklore through the story of Urashima Tarō, a humble fisherman who, in a moment of compassion, saves a sea turtle. In return, the turtle leads him beneath the waves to a wondrous island of immortality. There, time stands still. He weds a princess, lives in peace, and becomes untethered from the aging world above. But when longing for home overwhelms him, he returns to the land of his birth – only to find centuries have passed. No sooner does he set foot on familiar soil than the spell of agelessness breaks. He crumbles into dust.

This tale of timelessness, longing, and irreversible transformation speaks to something ancient within us: a yearning for permanence in an impermanent world. It is this longing – and the paradox it contains – that gently courses through these works.

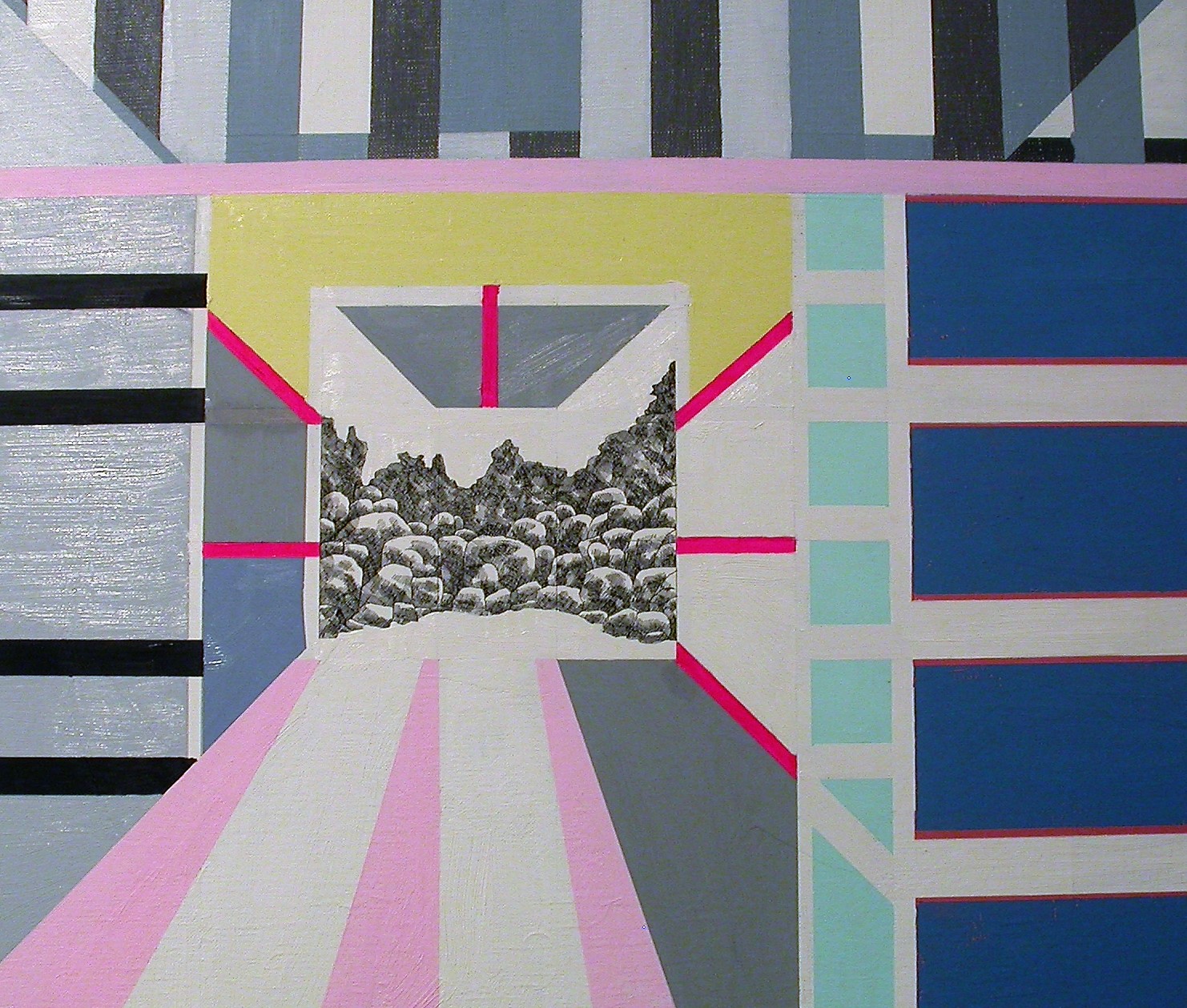

From the fifth to eighth century in Japan, the word for “garden” was shima – the same word used for “island.” A garden, like an island, is a contained world. It is both a retreat and a projection – a space of reflection, of ordering the chaos, of symbolically reconfiguring the vastness of nature into a form that can be entered, contemplated, and known.

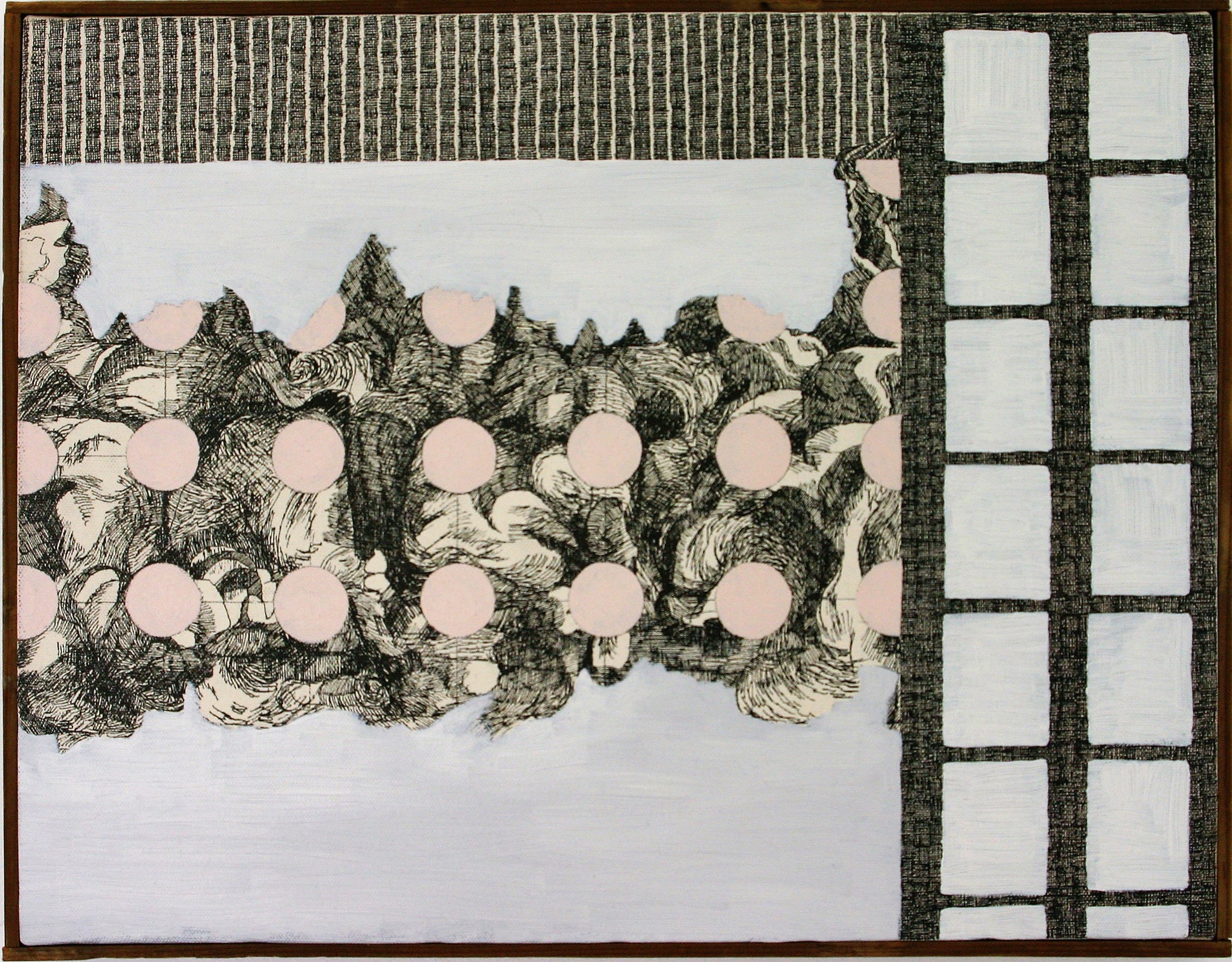

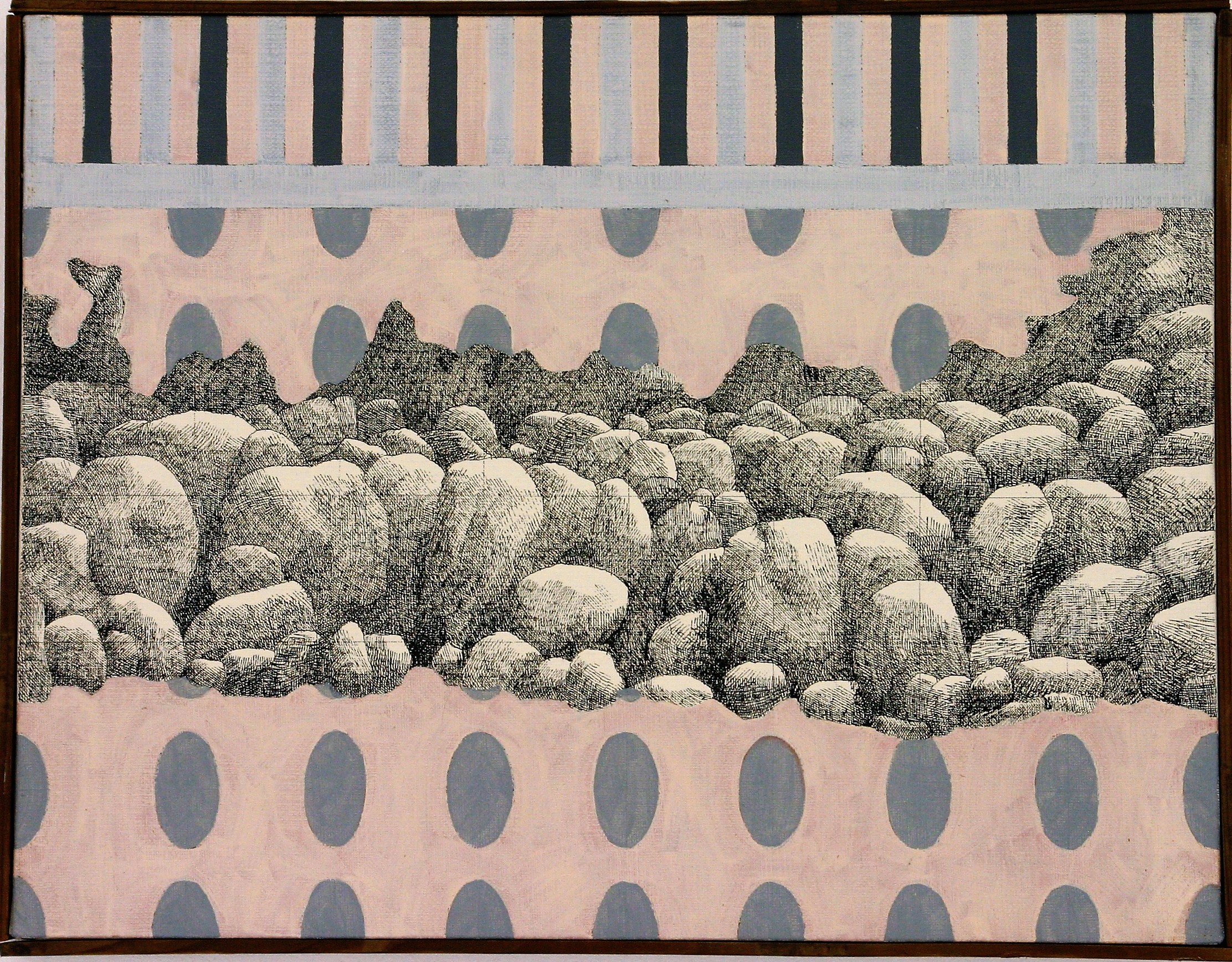

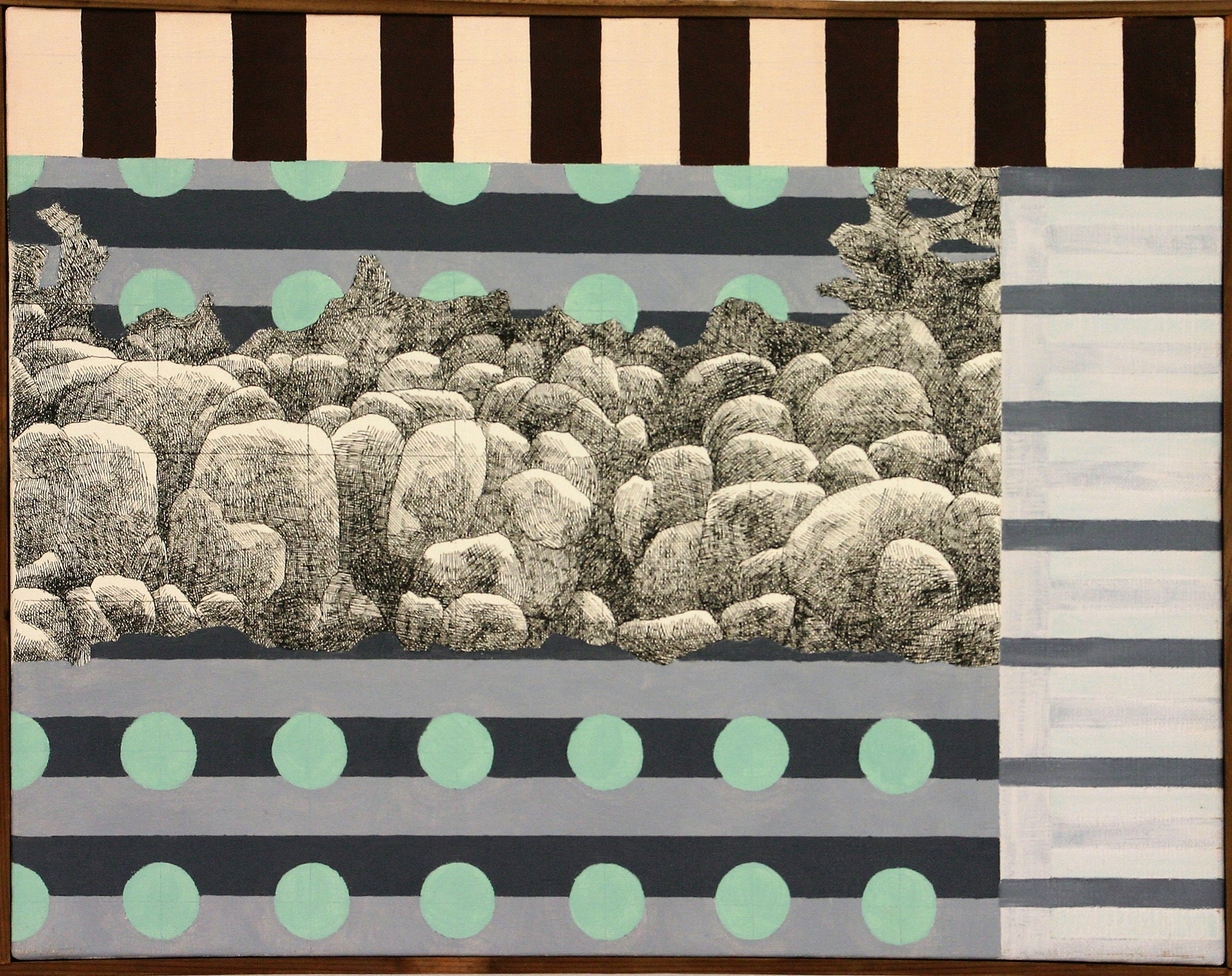

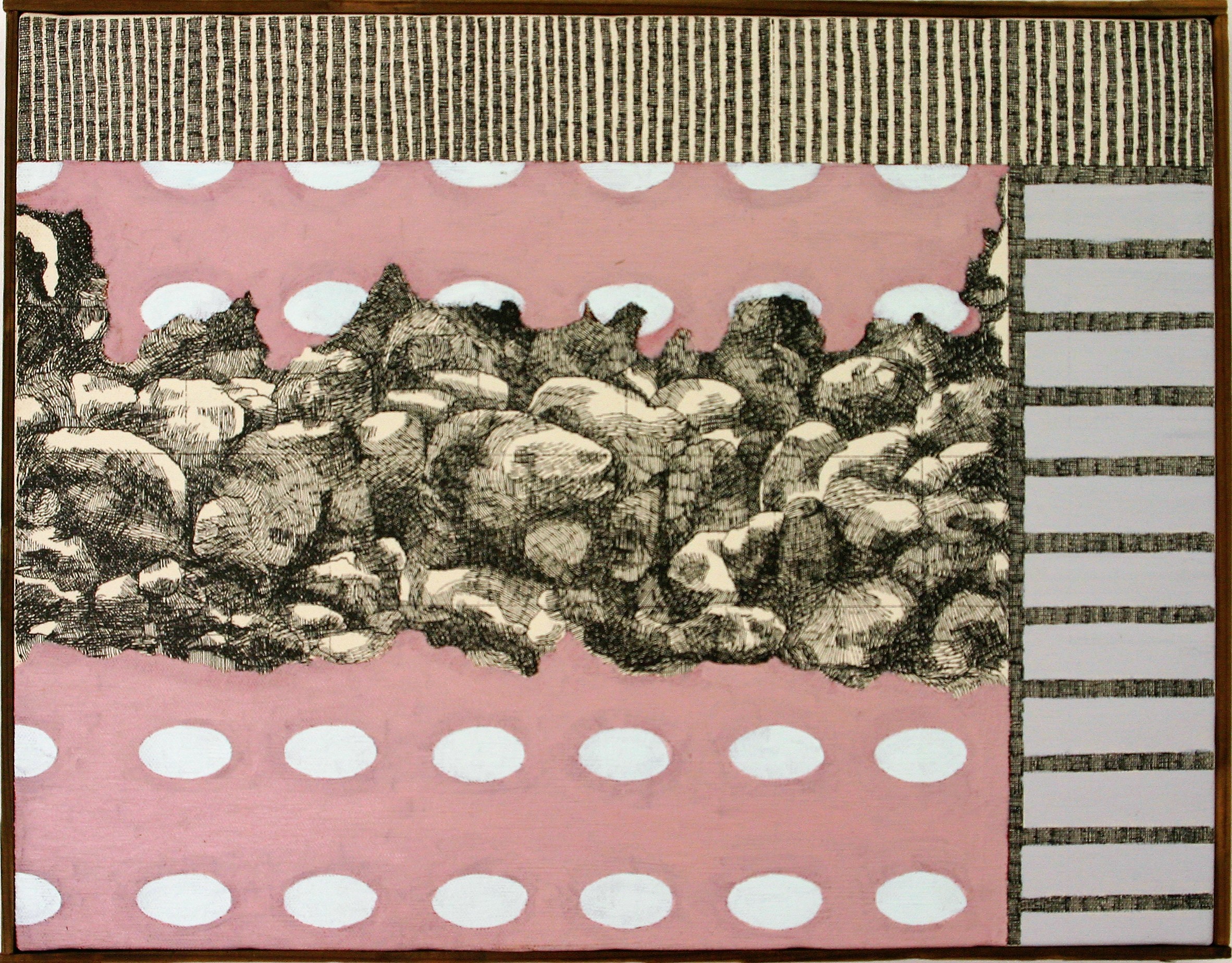

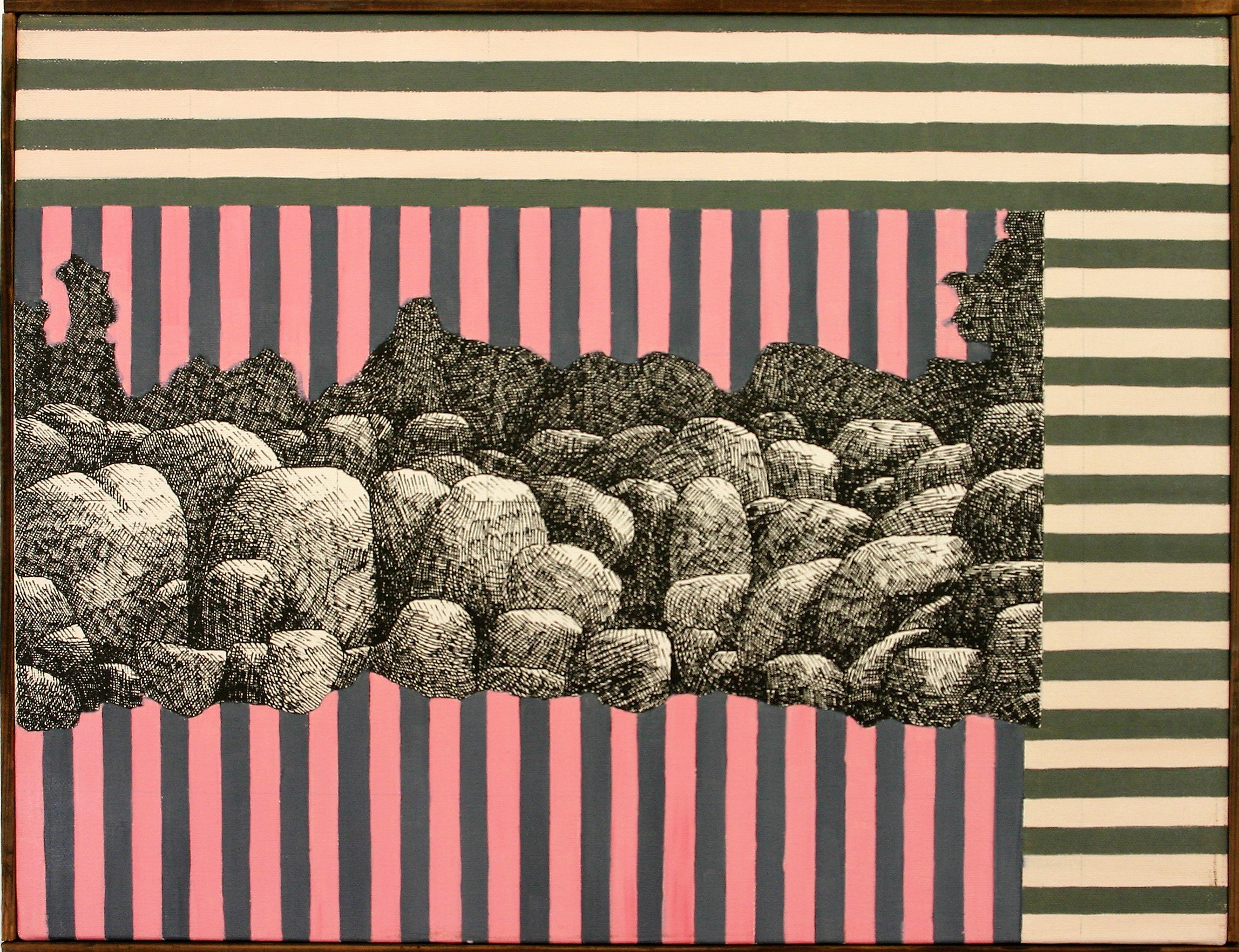

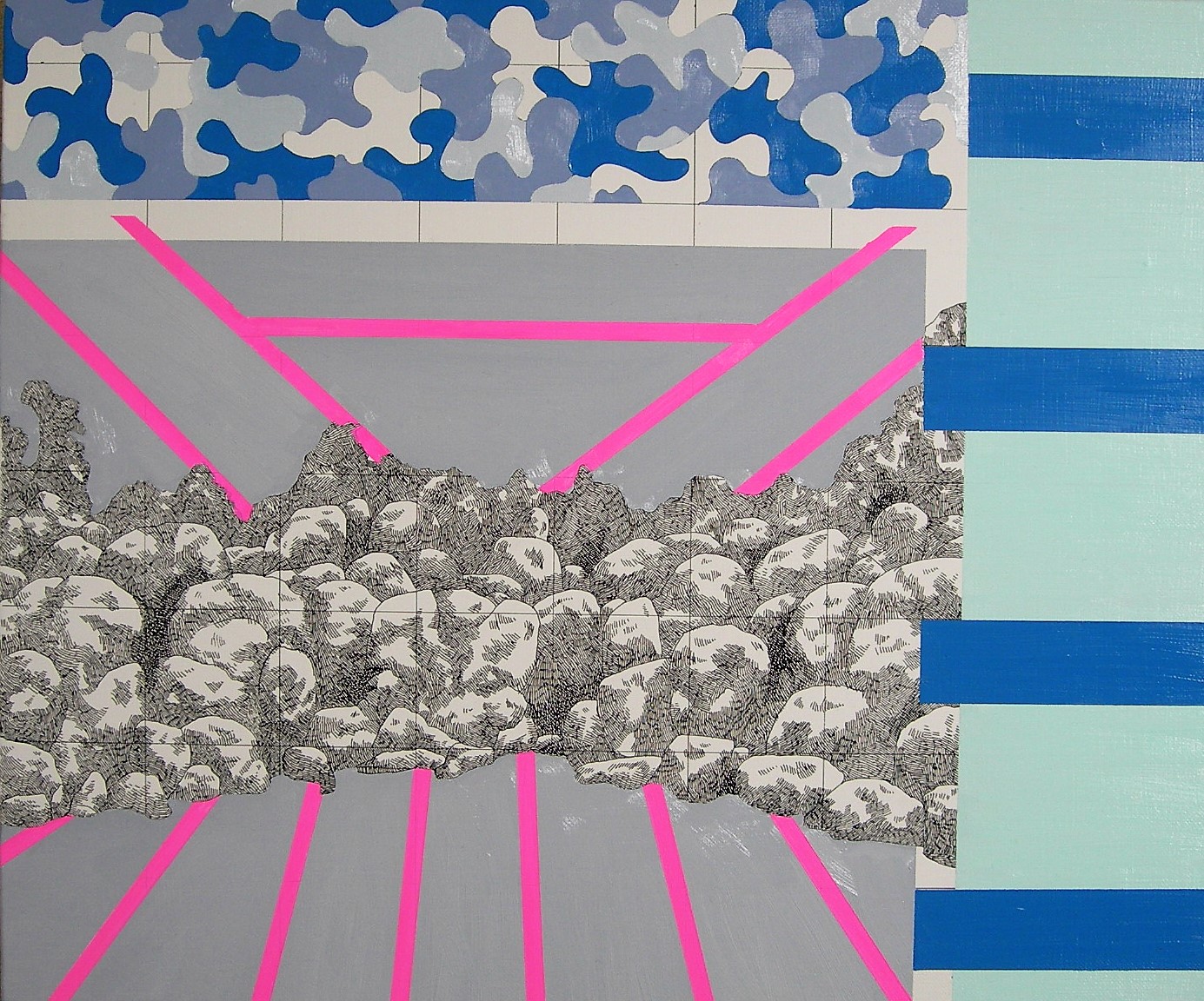

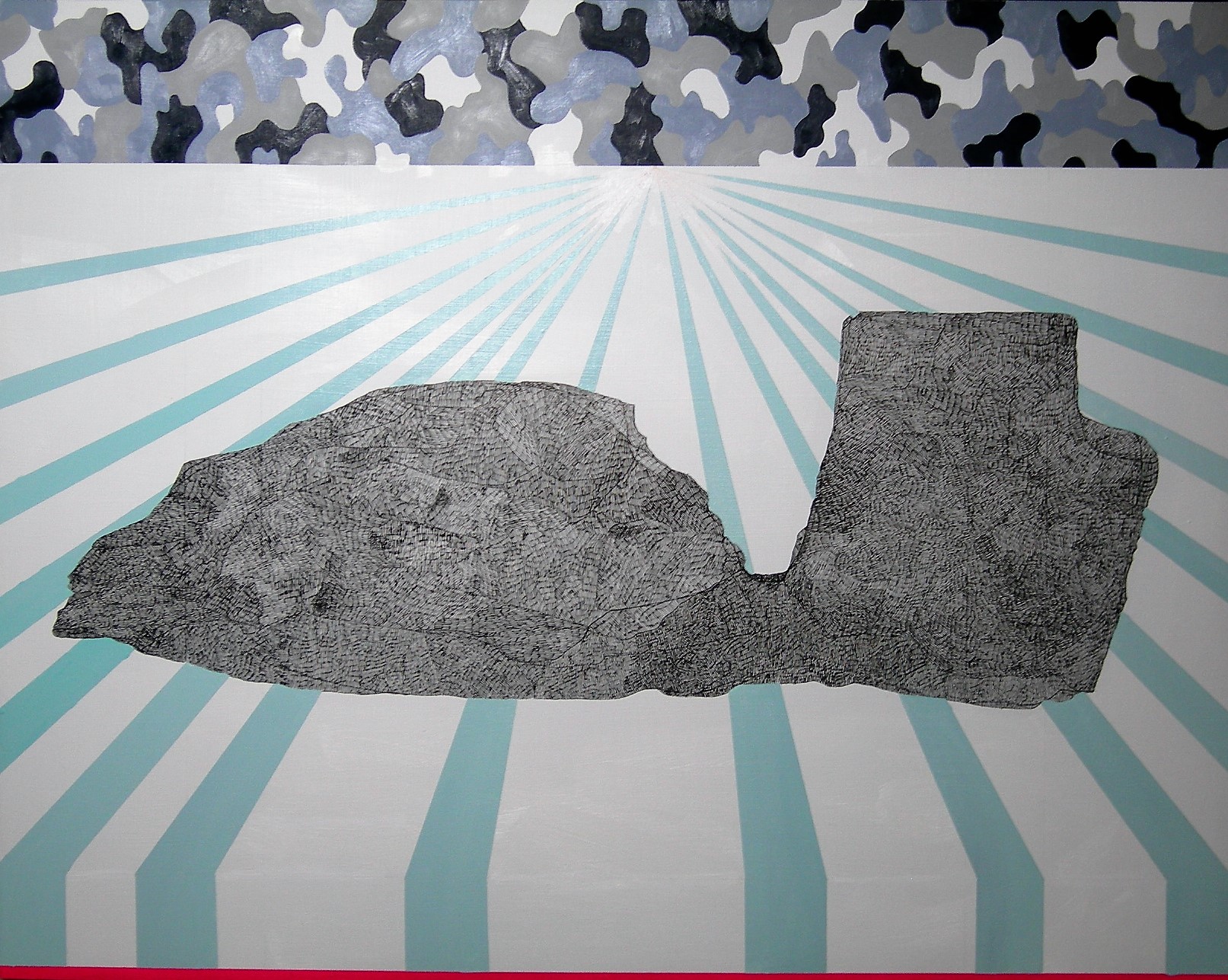

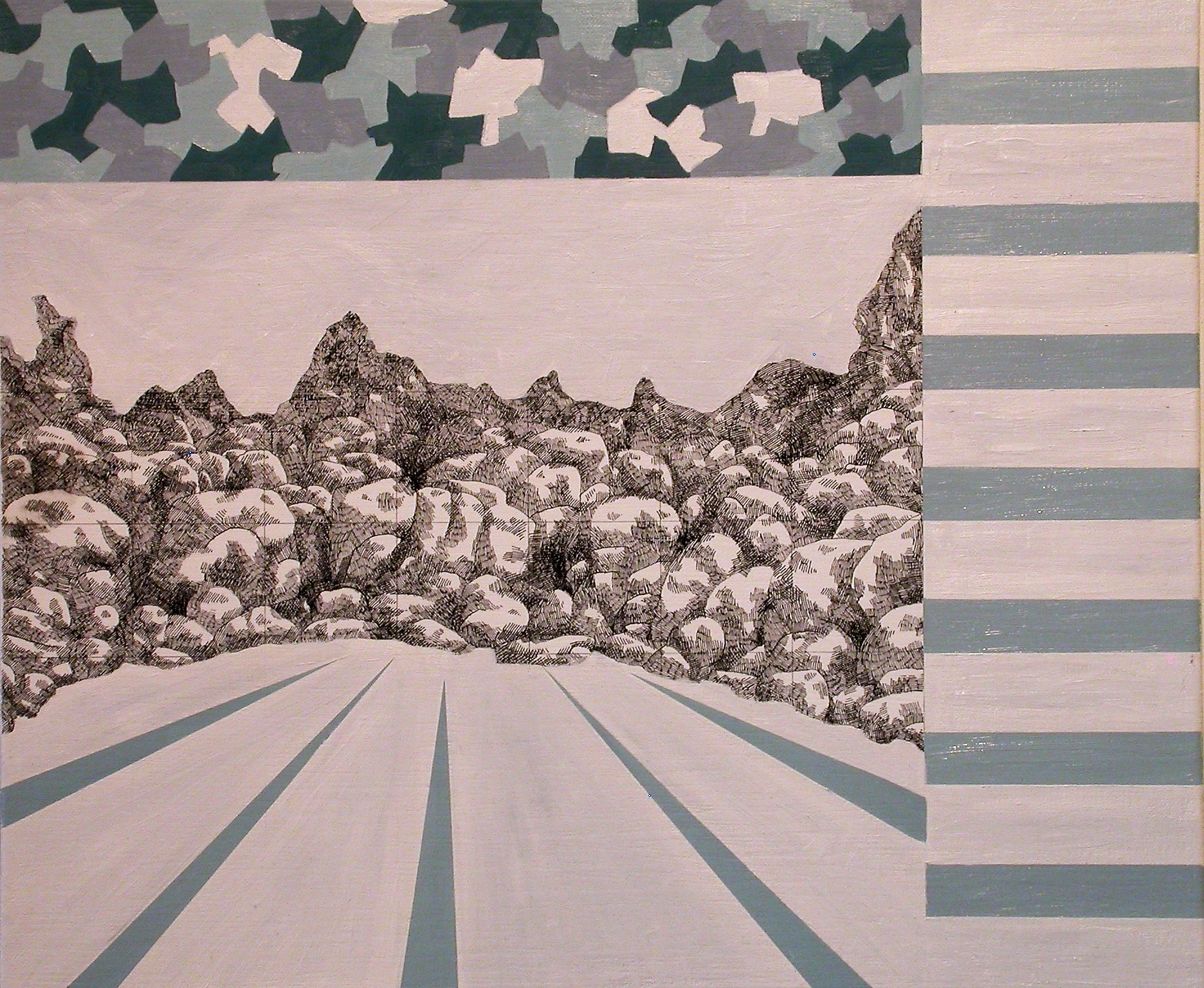

In this sense, the Zen rock garden becomes an island of another kind. Composed of little more than stones and sand, it nonetheless contains multitudes. Its minimalism is not emptiness, but essence. To sit before it is not merely to view a composition, but to be drawn into a different mode of seeing – one that reaches beyond form, beyond illusion, toward an intuitive understanding of nature, self, and impermanence. One begins to sense the islands, not as physical places, but as metaphors: for stillness, for insight, for the possibility of inner continuity amidst the flux of the world.

These works were created in Japan during a period of personal retreat. My studio was no more than a desk – modest, constrained, but quietly sufficient. In that small space, I practiced stillness. I accepted limits. And from that acceptance emerged a deeper mode of making – less about producing, more about attending.

The act of contemplating a rock garden became a form of drawing without gesture, a way of receiving rather than inventing. What entered the work was not merely form or symbol, but atmosphere. I sought not to depict islands, but to evoke their quiet presence – to suggest the weight and silence of a rock, the soft curvature of sand, the feeling of drifting just outside time.

In the story of Urashima Tarō, the islands remain unreachable, the immortals forever just beyond the veil. Yet through this work, through the contemplative gaze, we are offered a fleeting glimpse – an opening into the space between longing and letting go.