A Pattern of Extinction (2019) is a series of paintings and drawings that explore the relationship between cause and effect—between human progress and ecological loss.

In 1855, Sir Edward Knox founded the Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR) and began building his mansion, Fiona, in the affluent Sydney suburb of Woollahra. When European settlers arrived in 1788, First Fleet officer Daniel Southwell translated the local Aboriginal word (Dharug language) Woo-la-ra (also later spelt by others as Willarra and Wallara) as meaning “lookout”, but it has also been translated as “camp” or “meeting ground”. In contrast, Fiona means pure white – a nod, perhaps unconsciously, to the end result of refined sugar: whiteness through industrial purification.

Half a century later, in 1907, Sir Walter Rothschild published Extinct Birds, a book cataloguing species that had disappeared in modern times or stood on the brink. It was a document of loss and a warning of what might come.

In 1945, Mary Hutchinson gifted her nine-year-old grandson, Jacob Rothschild, a small painting of a hummingbird by Simon Bussy. It was the first artwork he remembered. His father, Victor Rothschild, a brilliant zoologist, had instilled in him a deep awareness of nature and its fragility.

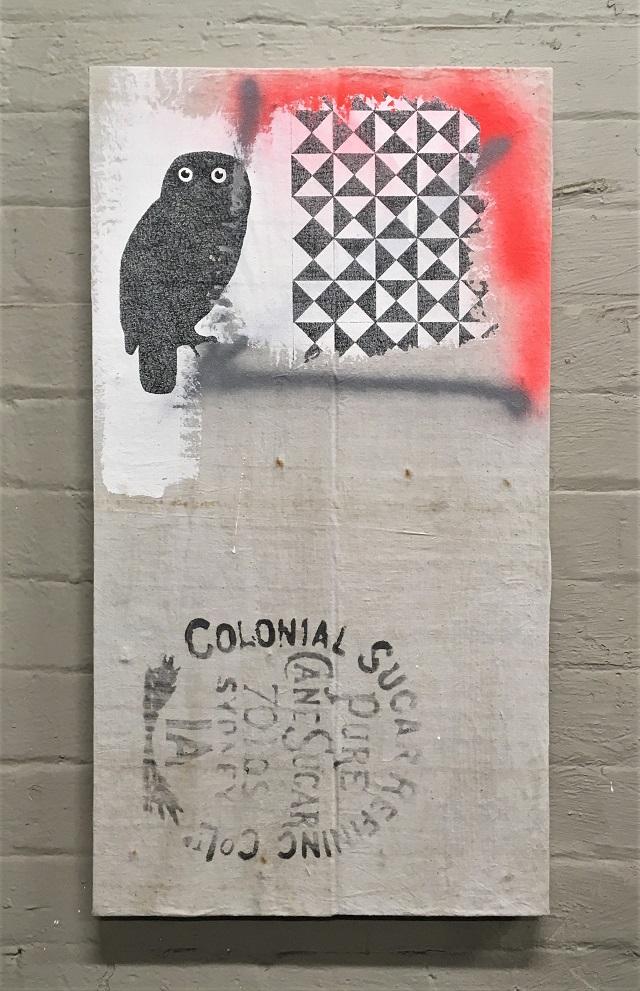

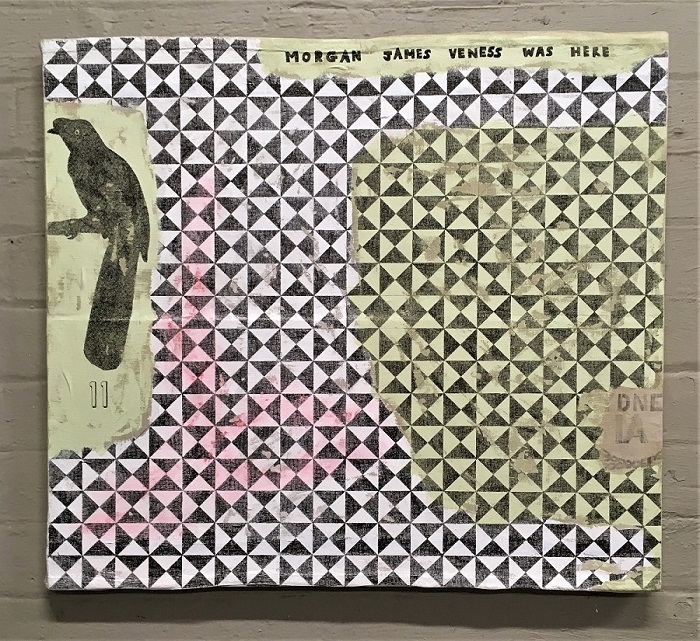

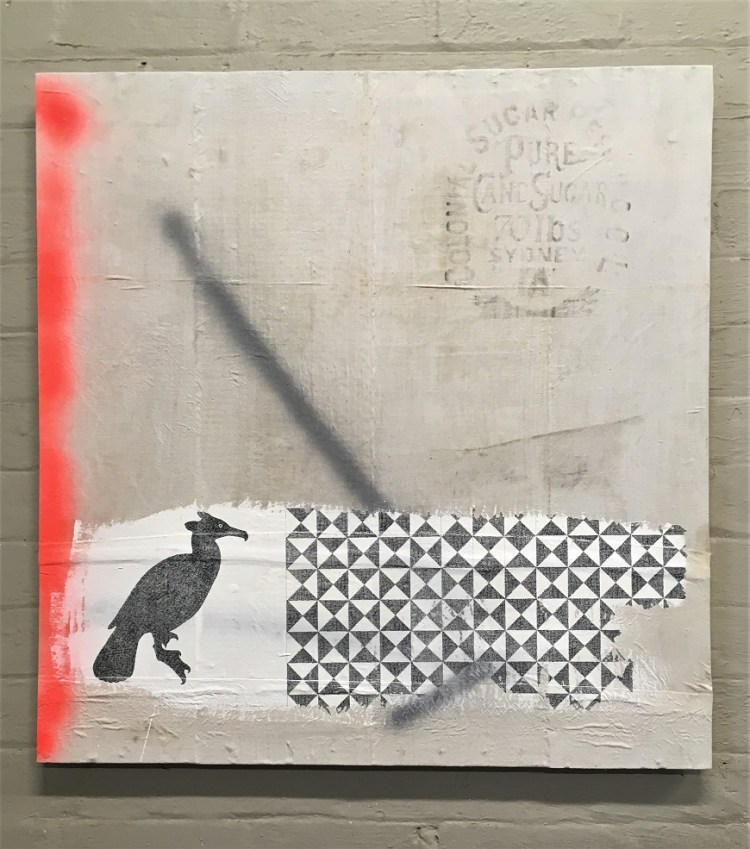

A Pattern of Extinction draws together these threads of history, science, and personal memory through a symbolic visual language. Each work centers on the shadowy imprint of an extinct or endangered bird, captured in a recurring pattern that seems stamped or fossilized onto reclaimed CSR sugar sacks—ghosts of birds preserved not in bone, but in fabric and pigment.

The materials themselves carry meaning: found sugar sacks are stretched over dismantled timber crates once used for shipping. These elements evoke cycles of trade, exploitation, and consumption. The series employs re-purposing not only as a technique but as a conceptual framework—re-examining systems of value and production.

The birds, though absent in form, are present in trace—their silhouettes haunting the surface. The checkered grids suggest a power matrix, a calculated order. Yet the soft painterly surface unsettles this control, suggesting beauty as a mask for harm.

As abolitionist Wendell Phillips famously declared in 1852, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” In this context, that vigilance is directed toward nature—toward what has been lost, and what may yet be saved.